THE ANSWER TO QUESTION 5 – IS IT MATHEMATICS?

This question was submitted by Rebus Frill Truckmen on 3 April 2024. They wrote: “I have been reading some RLS recently, to join the dots between idling and Bill Drummond. I stumbled across this question. Your help would be greatly appreciated”.

You can read more about 23 Questions, and see the Robert Louis Stevenson quote in context on the 23 Questions page of this blog. You can also submit your question(s) there.

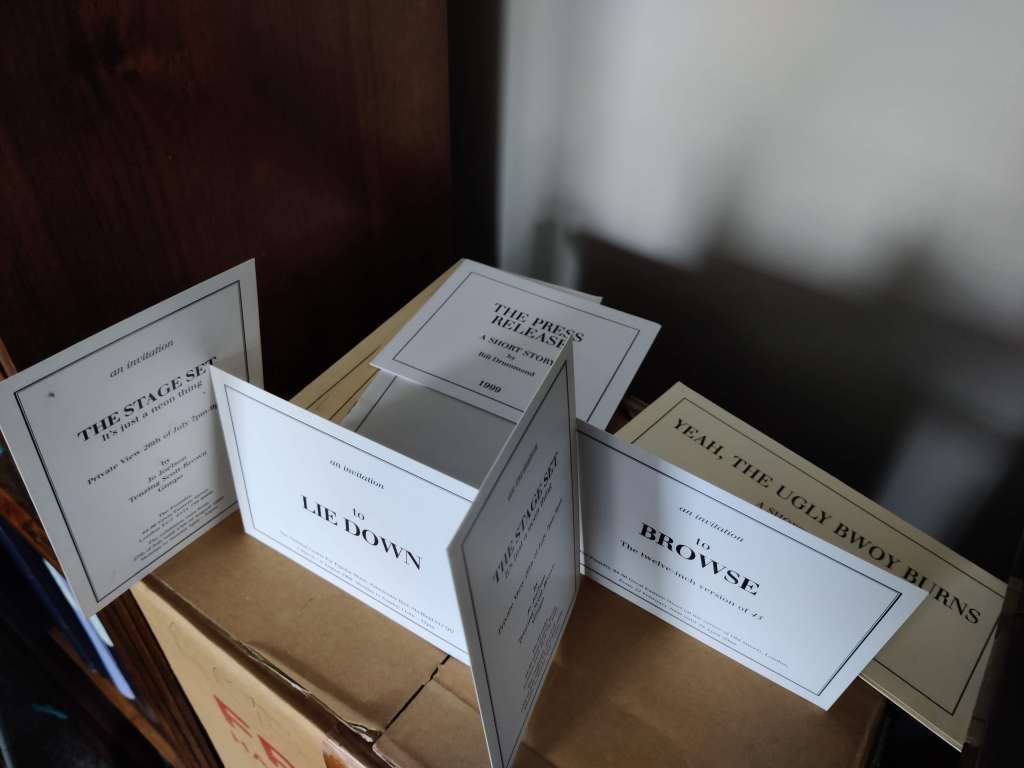

Note that Penkiln Burn pamphlets referenced throughout the answer can be viewed (albeit not in full text) at KLF.de.

But for now, I will hand over to The Food and Literature Delivery Rider, in a form of let and sublet agreement through The Benefaktor.

All will become clear if we’re lucky…

I have two phones. One for my food deliveries – an iPhone provided by a well-known food delivery company, securely attached to my handlebars in a waterproof cover (tricky to handle with the goat hoof gloves essential to survive an Edinburgh winter). And the other – a “burner” – provided by my father, The Benefaktor, for the literature deliveries. I manage a few hours a week for my first job. Not quite enough to produce the mental health boost that Gillian mentions in her pamphlet On/ Off Work. But my father supplements that quite enough to fill the eight hours a week. Over the pandemic it was deliveries of books from local independent bookshops, to lockdown imprisoned readers. When that dried up, I diversified. For example I might collect a tap from a wholesaler to allow a plumber to fix a sink for a student completing their English literature thesis. But to be honest that just happened the once, and it was for my cousin. Then GANTOB (the project) came along in 2023 and I had quite a busy summer, popping up to stationers for A5 coloured paper, pound shops for padded envelopes and dropping off pamphlets and books around Scotland. Clandestine operations sometimes – delivering a USB stick to a woman wearing a yellow carnation standing outside the Boots at Waverley Station. A message in a bottle to a man in a café round the corner from a consulate. All to maintain my allowance. My first documented drop off was to The KLFRS themselves.

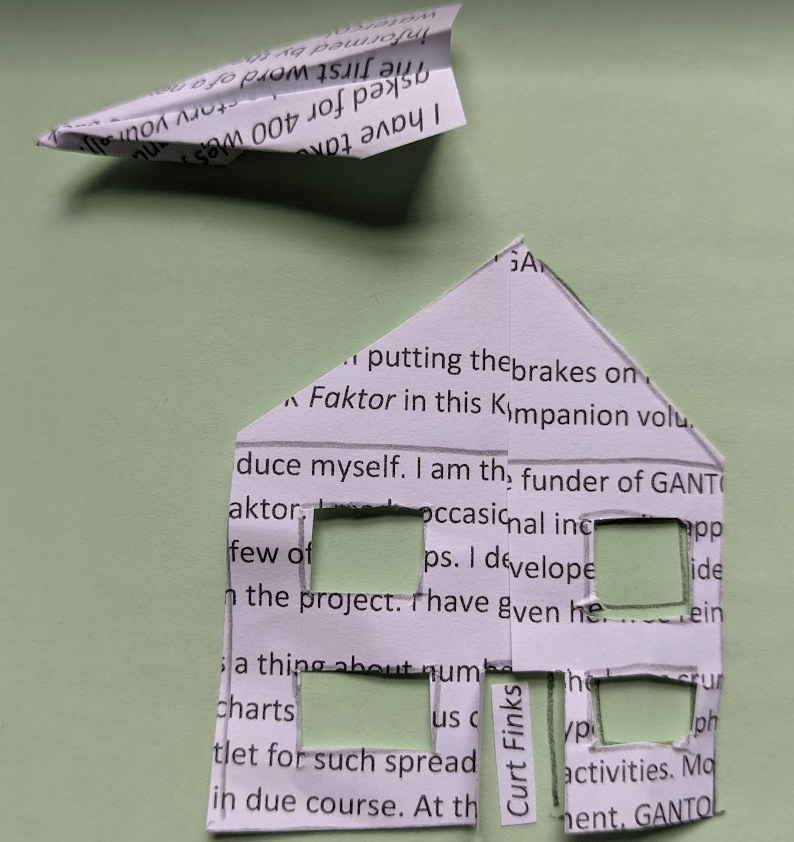

The most recent text to the burner, received on Wednesday morning, read as follows: “You’re needed now. My room”. I scuffed along the corridor and knocked on his door. He was wearing a thick towelling dressing gown and slippers. Old man hairy legs on display. He thrust a jiffy bag into my hands and retreated back into his room (“The Kino”). The package was addressed to me, using my name rather than function. It was unsealed. Inside there were photocopied materials, a handwritten letter, and a printed sheet containing some notes. It was an instruction, not a request. As usual, my allowance was conditional on successful completion. The diktat stated that I was to write the unofficial version of the subconscious section of I Am Forty-Six (under): for Bill Drummond’s memoir, The Life Model. I had been selected because I am currently 46-years-old and am a man. Fine. Mission accepted. As if I had a choice.

The Benefaktor laid out a few rules:

Your pamphlet can only include material relevant to the period (29th of April 1999 to 28th of April 2000).

It is not an official part of The Life Model.

It has to be written mainly from the viewpoint of a 46-year-old man.

As it is being written after the publication of The Life Model, and stands as part of the GANTOB canon for the 52 Pamphlets, it can provide some reflections on the period in question from the viewpoint of 2024, but remembering that you are still a 46-year-old man.

The word count must be a prime number.

The pamphlet must mention the number seventeen.

It must be structured – in whatever way you like – to represent the number seventeen.

Kreative Tyranny means that you cannot step outside that structure.

It must reference literature…

…and commercial dining, whether that is takeaways or restaurant meals.

Penkiln Burn pamphlets must be referenced by title and number.

Do not be confused by the stated publication date of these Penkiln Burn pamphlets; they cannot be fully explained…

…but try to find a plausible answer to the gaps in the pamphlet catalogue for that period.

Do not worry about “My Favourite Colour” (Penkiln Burn pamphlet 1): all the preparation had been completed by the year in question. It is a story worth exploring further in the future though.

Do not worry about “I Love Easy Jet” (Penkiln Burn pamphlet 2): I would view it as a flier rather than a pamphlet.

You do not need to mention The Press Release (Penkiln Burn pamphlet 6): it was the wrong shape and its predictions did not come to pass.

Do not try to extrapolate lessons about Bill’s Dad to your own relationship with your father, The Benefaktor.

Distribute the finished pamphlet with food deliveries on the evening of Friday 5 April 2024.

I Am Forty-Six (Under) (written from the perspective of Bill Drummond, as imagined by The Food and Literature Delivery Rider)

29th of April 1999 to 28th of April 2000

Sifting and sorting. Slipping and sliding. Sentimentality. Since I heard about Roger Eagle’s death from cancer, when he was just 56 years old, a few days after my own 46th birthday, my subconscious has been dwelling primarily in Liverpool. Some people have a disproportionate effect on your life – Roger Eagle had a powerful impact on me. Seeing others’ views in print after his death, or hearing them on the radio, felt like an intrusion on my grief. Simply Red, the Guardian obituary wrote, would have missed “a vital element in their musical education”. Shaw, as in George Bernard, was a distant relative. Sublime to the ridiculous, in reverse order. Still, that GBS connection is interesting. Significantly, Roger and I both seem to have lived by one of Shaw’s axioms: “A life spent making mistakes is not only more honourable, but more useful than a life spent doing nothing.” Stuff like that gets tucked away in my head all the time, waiting for the right moment.

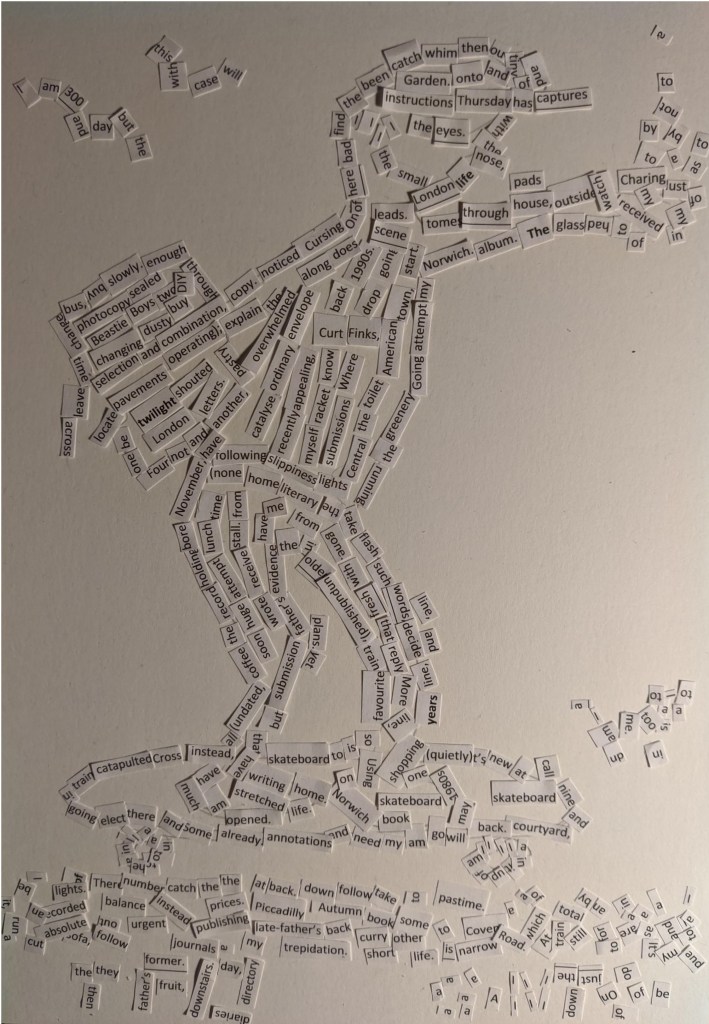

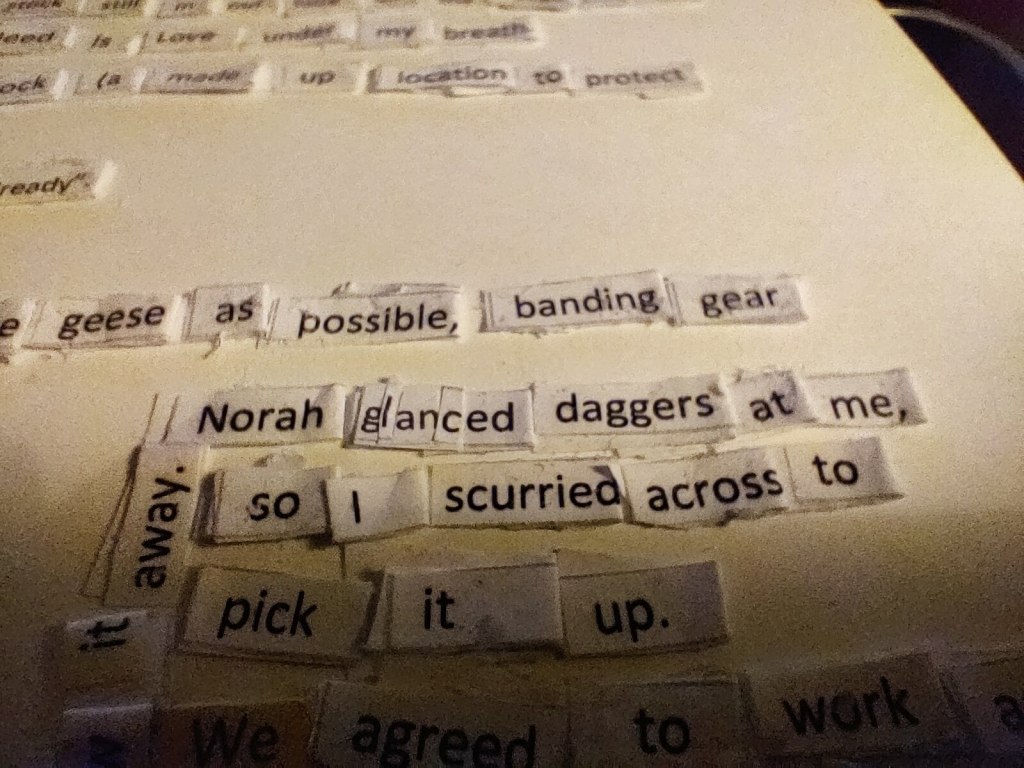

Eagle. Events of this year have hovered around his life and death, forcing pen to paper. Every twist and turn, documented in a pamphlet: memorialising, moralising, justifying, but also worrying about how it might be seen. Extemporising: “Maybe my idea is just me jerking off – ‘Look at me, Bill Drummond, didn’t I do well for myself’ – as I wave my diminishing wad at the thinning crowd”, even when that is unsuspecting customers at a snack bar or mourners at a memorial service. Escaping too – from responsibilities and a custodial sentence. Even my relationship with my eighty-six-year-old Dad, helping him to make sense of pieces of writing that he has collected in a box from across his life, sellotaped onto the page to create a… and I’m struggling to think what it is – a patchwork?

Version: that’s it! Versions of ourselves, through our writing (a book for my Dad), my book 45, or record collection in Roger’s case. Visions vary depending on who you ask. Vitriol and scorn if you don’t capture people’s heroes the “right way” (as I find out to my cost). Vacillate? Validate? Valorise? Vandalise – that’s where I end up taking my emotional oscillations about Roger, scrawled on a wall, numberplate caught, standing in court. Verbosity ignored, chapter and verse delivered. Victimhood? Vindication? Valediction is most on my mind, now and forever: for Roger, for myself, and for my elderly parents.

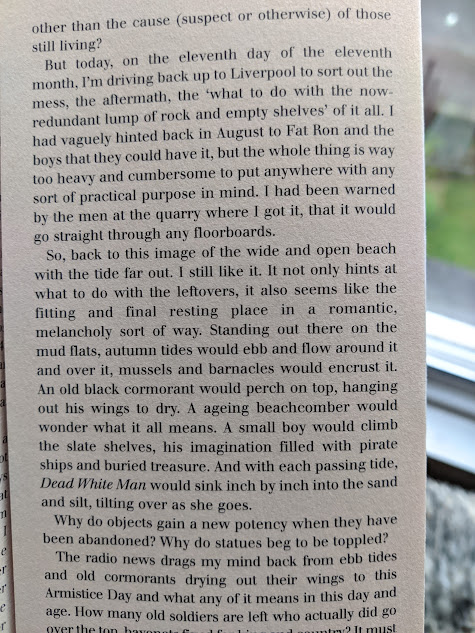

Eagle would have loved the sculpture I am planning for him I think, even as an Antony Gormley pastiche. Exhibit 1 from 17 Forever (below). Ebb and flow of waves, lapping at the base, submerging the record of a life, taking the covers and labels first, then salt between grooves, sand smoothing away the tracks. Eons of wear required perhaps, but probably still faster than the destruction of drips onto a box of papers stuck in a loft for decades, bookworm tunnelling, ink leaking, paper rotting, into mulch. Even if rescued from that fate, the box of my Dad’s papers risks a similar destiny eventually if my plans come to pass. Enforced exile in an oak box in the Eildons. Except, now we need to fast forward the future.

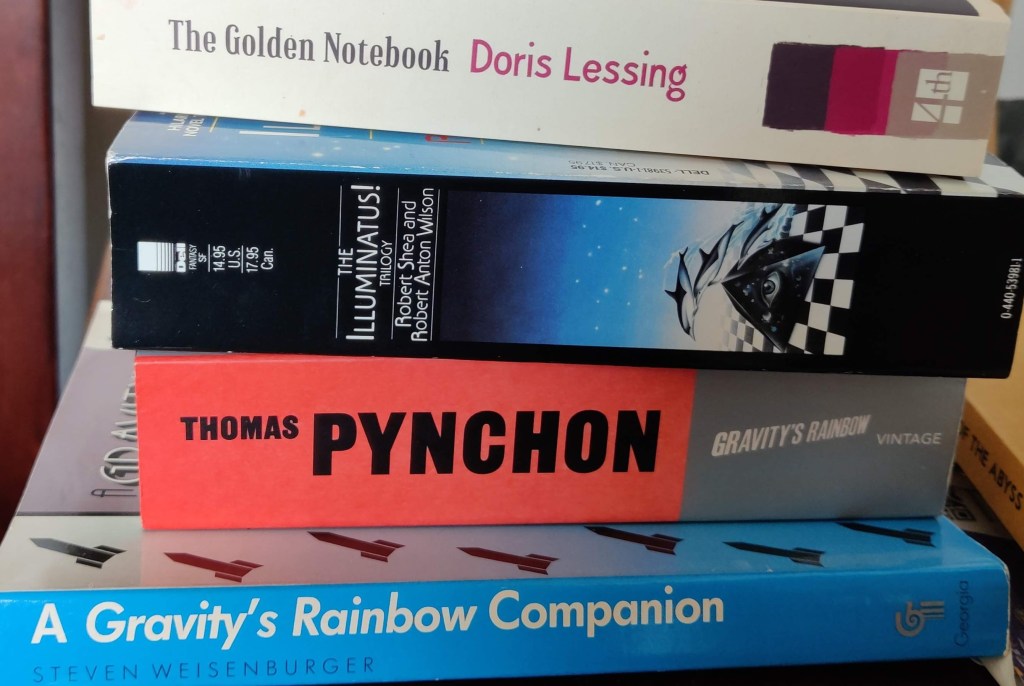

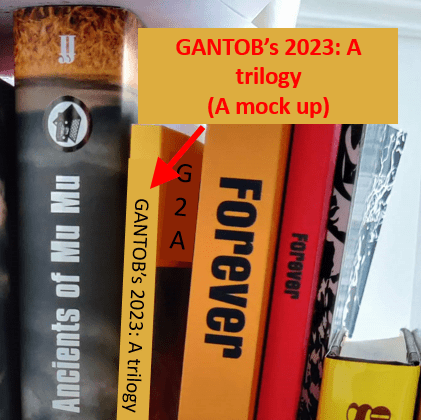

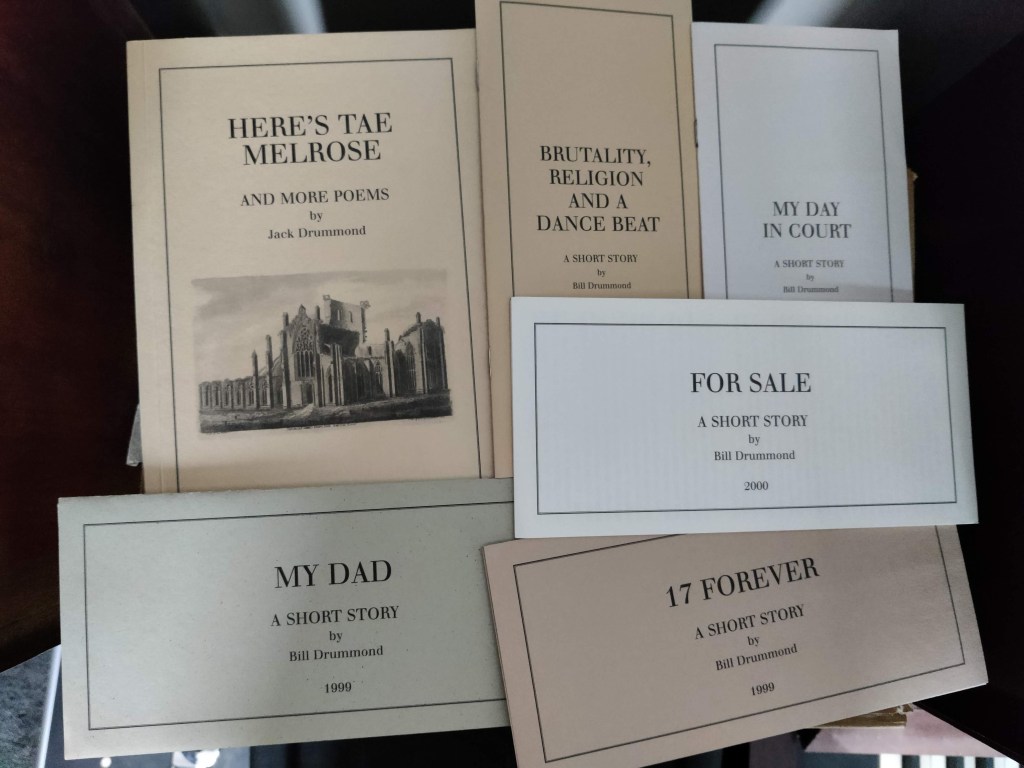

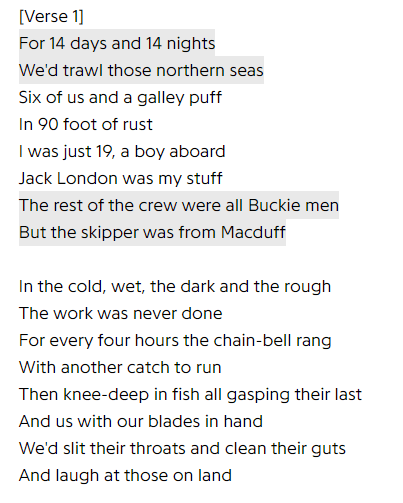

Nineteen-ninety-nine might seem a long time ago. Now, in 2024, after publication of my book The Life Model, I cannot recall whether my repeated mentions of the number seventeen in my writing throughout 1999-2000 were intentional or coincidental. Notes, from pamphlets published that year, document other men at age 17: soldiers lost in the trenches in the Great War, listed on war memorials across the country; my Dad, given his “first run out with Melrose Rugby Club’s senior side in the opening game of the 1930 season”; and a boy, white faced, sitting behind me in the waiting area for court room 17. No escape (from the justice system, or the number). Numbers – especially prime numbers – have always fascinated me, but I took extraordinary measures for the pamphlets in 1999-2000, after laying the ground with 17 Forever (pamphlet 9) and My Dad (pamphlet 10). Neatness was a driving force, which perhaps sits uncomfortably with my reputation as iconoclast. “Need” is a tricky word, but at the time I desperately needed my follow up pamphlet to 17 Forever (on Roger Eagle) to be pamphlet number 17. Nothing else inspired me at this point – I was drowning in loss, actual and predicted – so I couldn’t fill the gaps with words. Nudging things along, I devised a plan for five of the intervening “pamphlets”. Necrolatry was in the air, so I listed three pamphlets on death in the Penkiln Burn catalogue – Who Died Last (Penkiln Burn pamphlet 12), Paint Them Black (PB pamphlet 13), The Birth of Death (PB pamphlet 14), bookended by two “blanks” (PB pamphlets 11 and 15). Null returns, to represent loss, dust to dust. None issued, or even written. Number 16 in my pamphlet series was just a diversion in Correx at that point, attempting to salvage something from a $20,000 picture by Richard Long, framed as a “minor stunt”: it would of course become something much bigger, ultimately perhaps also buried in a box, but that is a story for another year. Number 17 of the pamphlets was the big show in town: My Day in Court, closing off my Roger Eagle stories in a blaze of glory – graffiti, and potentially time in prison. Not, however, my “Band on the run” moment: “Is this all some sort of publicity stunt?” they asked. No, but it would take another few years for me to find my real purpose with the number 17: a choir. Not that it would always involve 17 singers: where’s the fun in that? Nevertheless, unabashed by criticisms of my self-centred ways, I kept on distributing my writing, with pamphlet 17 going to diners at Cook Au Van; perhaps just to be crumpled up with packaging and discarded menus.

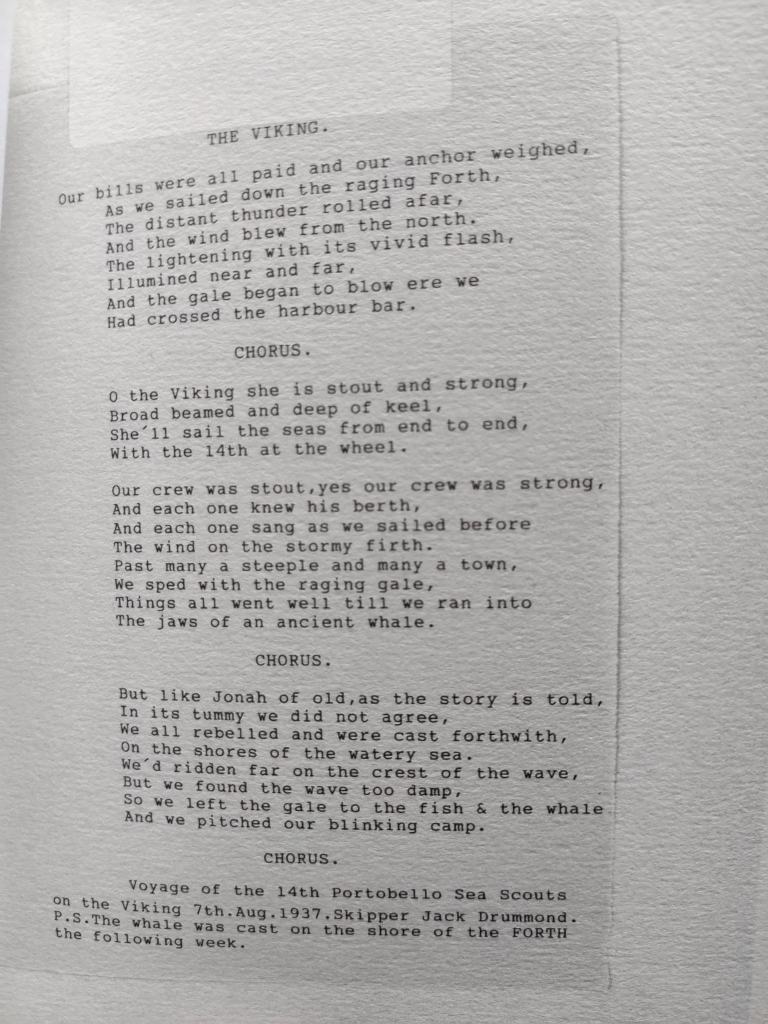

The work with my Dad was a welcome escape. Telephone discussions late into the night, agreeing the pieces to include. Things we had never discussed – his writing from the 1930s – drew me in. Thoughts about the impact of his verses on my own creative output. The rhythms in his poem The Viking (1937), for example, remind me of my own seafaring song The Porpoise Song (1988), when I was part of The JAMs.

Eventually he had a book (Here’s Tae Melrose), and a pamphlet to go with it (My Dad). Everyone has a book in them, and my Dad no doubt had more than that: if you were to sew up all his sermons they would make several volumes. Everybody in Melrose was to receive a copy of his collection of poems, but I don’t think that we managed that. Existence and presence was enough: we had the boxes of books and they rested in bookcases of some households in the town, but also of family and friends further afield.

Existence and presence: the hard copy of something that we produced together. Even now, 25 years on, it brings back happy memories of my Dad, and our conversations from throughout his life. Evidence of his long time on this earth. Edinburgh, Portobello, his – and eventually our – time in Africa, back to Newton Stewart, Corby, and destinations along the way and further down the line.

Nonsense poems, hymns updated to cover topical issues, the approaching millennium. News bulletins from my Dad’s brain. Next to my books in bookcases, and Penkiln Burn libraries, this volume, signed by my Dad, with a cheery greeting in each, stands as a record of the man as he was, as he thought and wrote and spoke and interacted and entertained and preached and comforted and consoled. Nothing can take that away. Now, in 2024, looking back, I can see that my explosion of pamphlets in that period 1999-2000 – however inconsistently numbered and inexplicably fixated on the number 17 – was driven less by Roger Eagle’s death and more by my subconscious concerns about what came next for my elderly parents, Jack (d.2009) and Rosalind (d.2010). Not forgotten.

1339 words (a prime number)

The Food and Literature Delivery Rider, 5 April 2024

Pamphlet 26/ #52Pamphlets

Answer 5 of the 23 Questions

Twinned with BOUNCE (#GANTOB2024 pamphlet 25)

One of the 9 Missing Years

This is an imagined account, inspired by, but not an official part of Bill Drummond’s memoir The Life Model (2024)