Gimpo – as ever – was the one who had to keep an eye on everything while the other two swanned about. After beating the bounds and congregating, he sent us all towards the Ferry while he made off back to the van. It wasn’t the best evening for a Krossing on the Ferry. It was rough as fuuk. With each step I took the boat would either rise to meet my foot, or swoop away causing me to wobble and go off-kilter. I stood close to the Panda and kept one eye on my precious niece. By now she had submerged herself into the madness and was wearing a retractable traffic cone on her head, tilted to the side like a fine hat and fastened underneath the chin. Like me, she was no stranger to mishaps. She had the biggest of smiles as she took in the madness around her. I could still feel her pain though. We were all called to silence as the roll call of names ensued and the lights from the Liver Buildings shone bright across the water. We gasped and gulped as my brother’s name was read out among the names of those to be Mumufied this year. A reminder that he was gone.

I’ve often gathered my family together in the autumn months to take the Ferry ‘cross the Mersey to remember our Dad/Grandad/Great Grandad. At least one or two were obliging most years. I didn’t go back to Liverpool much since I left in 1994 when I was 21. I tried to keep it to once a year. If someone died, was born, married or had a significant birthday then I was usually persuaded to return more often. I like a family party, even if it is a wake. It is nice to see everyone together and remember those who have passed. Talking about the good old days.

One year, on a bright and balmy October afternoon, I managed to get at least 10 of us together, and we took the Ferry to the other side, and back. We never got off the Ferry, straight back to Liverpool and then off out for tea: that was our tradition. This time our Ray even made it. He never had before, and he never made it again. This year he was on his best behaviour and made it to the Ferry terminal to meet us all there. He wasn’t even gouging out or rattling too badly. We posed for photos, all four siblings, even some of our kids. My mum loved it and thanked me for arranging everything. Just as we were about to pull back up at the waterside, before the sound of the chains, and the smell of the oil, Raymond disappeared into the toilet. We all got off the Ferry and looked around for him. Eventually, he came skipping down the gangplank. He was fuuking muntered. He was smiling and laughing. My Mum announced his full name while rolling her eyes. Most of the family muttered in unison, “Oh for fuuk’s sake”. I took him by the hand and led him along with me, asking him how he’d been and if he was buzzing? “Yeah!” he nodded. I was long past being angry with him for being an addict. I saw it as a potentially permanent, terminal illness that deserved empathy, understanding, the odd chin wipe and a constant stream of £20 handouts. As I said, I didn’t see them often, so it was never too onerous to endure. I loved my brother dearly; we were best friends all our lives.

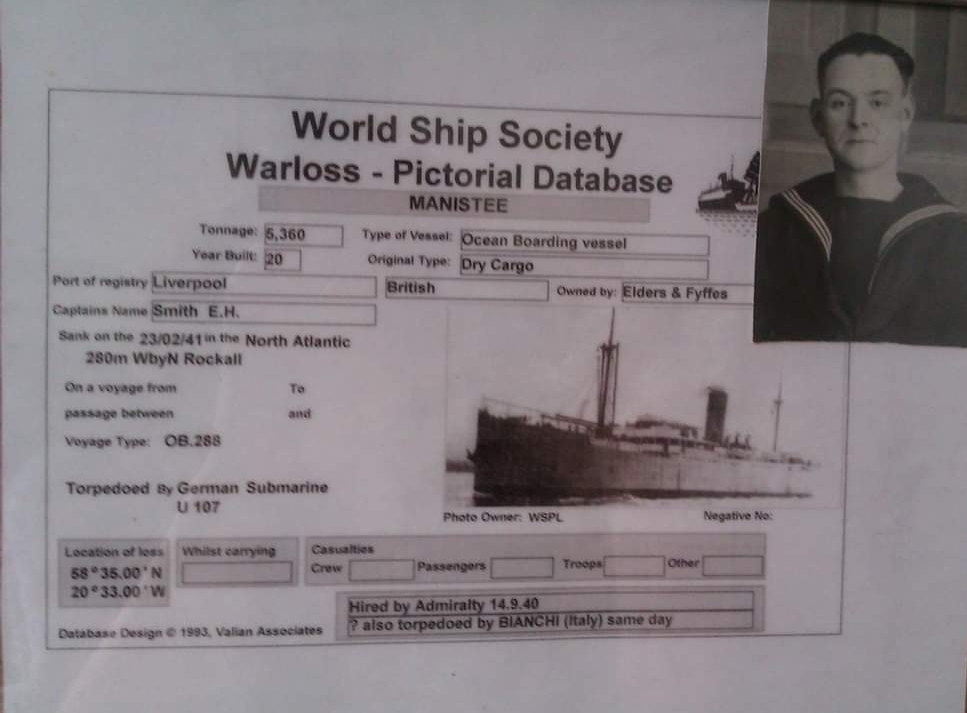

Dad was still holding my hand as we walked off the Ferry. I felt him walking slower than me, so I tried to slow down. It had been like this for a while now, but I didn’t ask too much about it. I just walked slower or sometimes I would take a step forward and then back – a bit like Scottish dancing where you take two steps in the same place before you move along – but slower and still holding his hand. I noticed how Dad’s hands had become smoother than they used to be, even the traces of oil were gone from his nails.

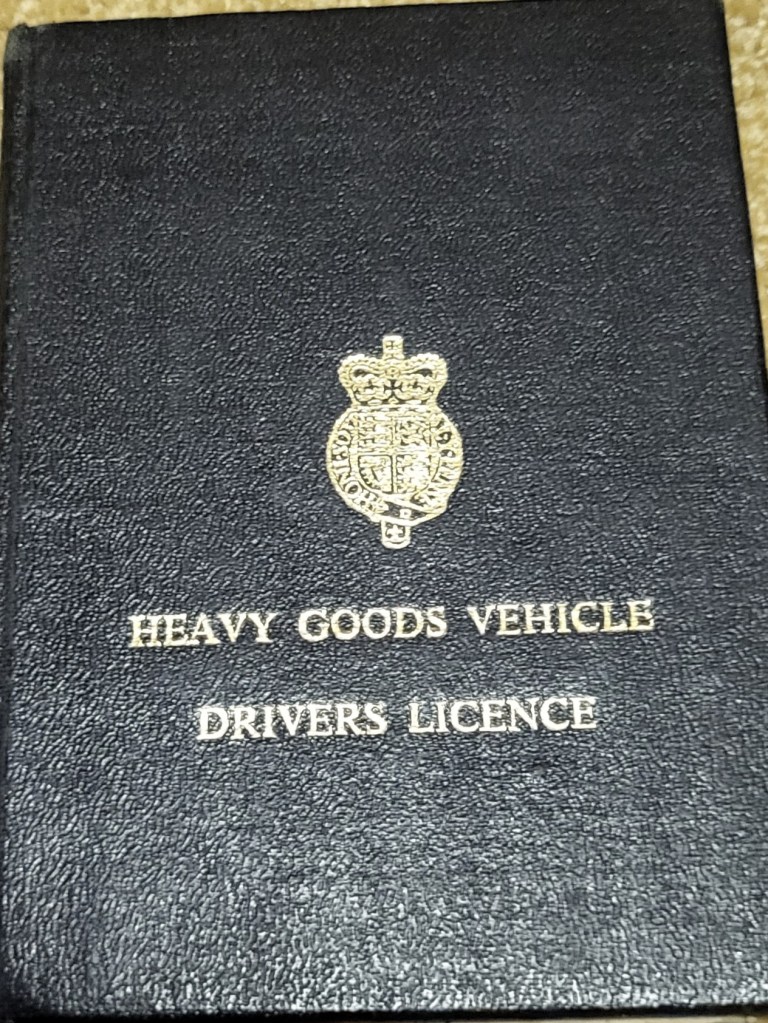

He hadn’t fixed a gearbox in ages. I missed having a Scania parked at the end of the path. I was always proud to show off Dad’s lorries to my mates when he brought one home and would use my acrobatic skills to get up to the cab, informing my friends that they were not allowed up here. I’d smile at myself in the large wing mirror and enjoy the smell of the cab.

We walked along the waterfront, looking across to the other side, Dad informed me correctly that it was the best view in the world from over here and the poor sods from Birkenhead didn’t have it all that bad: at least they get to look at Liverpool. The view from our side of the water was pretty grim. We called Birkenhead the Badlands. It was really fuuking grim in the 80s: everything was. Dad had to sit down. I could see it was upsetting him, so I declared it was time for another sandwich and some of Auntie V’s homemade delights. He agreed and I was even allowed to hold the Kiaora bottle this time. We sat looking across the water, thinking to ourselves, munching away on Viennese Whirls and Battenberg. Dad finished off the butties too. Divine.

Summer came and went. Dad took me to see my other aunties, one by one. We had a lot of days out me and Dad that summer. I had to start the big school. It was a convent school. I was dreading it. I had heard about the Nuns from my sister. She was 12 years older than me and had been taught by the same nuns and so had my brothers. The Sisters of Mercy. I had been informed they were merciless. A few weeks into term, Dad got a date for his operation that was going to make him better. I was assured by everyone that he would soon be right as rain. I love rain.

At last, I heard the chains clunk. We were waiting by the exit keen to get off. A girl ran past and shouted “Fuuk that boat!” as we disembarked. It was a rough crossing. As instructed we walked slowly and in an exaggerated manner along the landing pier and out towards the Badlands. The choir from Toxteth was waiting on the other side singing aloud, informing us that “one day like this a year would see me right, for life”.

Me and my niece locked into a hug and wiped each other’s tears. “That fuuking boat though!” we laughed and wretched in unison. The ice kream van chimed the tune of Justified and Ancient, and a police van tore towards the terminal with its siren and lights. It wasn’t for us. We were all surprised. Flares were going off, smoke and colours. We collected my brother’s brick. He was heavy, I’m not going to lie. The pyramid led the way, on a forklift truck of course. I followed the crowd and I found myself walking along a strip of the waterfront I hadn’t walked down since 1983, when I was with my Dad. I thought of everything in a flash that had been and gone over the 40 years since I was last here. What had life taught me? I realised all at once the knowledge I had gained, the stories I had seen unfold. I wasn’t sure how, but for that moment, I knew. The tears streamed down my face. The Panda saw them and wiped some away and nodded his big Panda head. That Panda took care of me. He fermented foods for me: pickles. I like pickles.

Dad died just before 8 pm on Tuesday 25th October 1983. Karma Chameleon was number one in the UK Charts and Dolly Parton and Kenny Rogers were number one in the US Charts with Islands in the Stream. I sat in my bedroom with my pull-out poster of Boy George. I didn’t cry. I didn’t cry for years after that, not properly.

CHRISTINE, 4 May 2024

Pamphlet 38 of the 52 Pamphlets

Part of the answer to question 18 of the 23 Questions

This concludes Christine’s wonderful SaveAways trilogy