Cover image is by Gaynor, as featured on the cover of the second GANTOB book.

Little Grapefruit has rejoined the GANTOBverse in an attempt to complete one of the “9 missing years” from Bill Drummond’s memoir. This is the first of those years, though we’re answering it midway through the project. Little Grapefruit reports back from an imagined Bill Drummond, somewhere in his infancy. It is Year Zero: 29th of April 1953 to 28th of April 1954. We’re in Butterworth, South Africa.

Little Grapefruit’s piece is called Bounce. As with the other pieces in the 9 missing years project, there is nothing official about this pamphlet. It is written after the “publication” of The Life Model. It was imagined on 3 April 2024. It has nothing to do with Bill Drummond, though it is ostensibly about him. Instead, it is part of GANTOB’s 52 Pamphlets. Oh, and the 9 missing years project of course.

To complicate matters further, Little Grapefruit’s pamphlet answers a question that she posed herself – question 4: “What is rhythm?”. But she wants to change the question to “what is rhythmic?”

Though against the laws or Kreative Tyranny, I have allowed this change. There is no stopping Little Grapefruit.

Finally, though this is a Little Grapefruit story, it is not really for children. They might not appreciate the technicalities. Fortunately, by the time you get to the third or fourth line they will be off trying out some tricks with bouncy balls or, if you’re unlucky, grapefruit.

Over to you imaginary Bill (AKA LG):

BOUNCE (AKA What is rhythmic?)

Rhythm.

Bouncing around like a rubber ball. That’s a complex rhythm. That would take complicated maths to work out. The long gap between the first and second boing, slightly shorter for the next, with each successive contact determined by the height from which it was dropped, the surface, and the “geography”. Try it in a long marble hall or against the corner in a squash court and you will achieve quite different results.

Unfortunately grapefruit don’t really bounce. Please don’t try it out.

Counting out rhythm can be quite complicated. I wasn’t ready for the Kodály method; all these “ta, ta”, “ta-o”, “ti-ti” notes. When it was clear that I wasn’t going to connect with these basic lessons, I tried to unpick the music that was playing on my parent’s radio. Learning in practice. Kodály would have written out “ti-ka-ti-ka” for the first notes of the second bar, or should that be measure? And what about hemidemisemiquavers, or should that be half-thirty-second notes. I don’t know, and I can’t ask anybody. Theory isn’t going to work at this age. “Keep it simple stupid”. That’s the advice that I babble out. Focus on the sounds that are all around.

Music for babies should not be Mozart or anything else predicted to produce geniuses. It should resonate with the baby’s subconscious. And for any infant, myself included, that means the sounds that have been all around since we could first detect the outside world. This is the universal language well into infancy, reminding us of the time spent in utero. The beats dissipate through the first few languid months, like the reduced force of a rubber ball, bouncing till there are only echoes, like whispers of ancient Greek, in mountain villages, by the Black Sea, Romeyka. Spoken, by a few…

In the black sea of my mother’s womb I was aware of vibrations early on. The fast beat of my own heart a month into my stay. So fast that initially I wasn’t aware that it was something flowing. No wooshes. Just snaps and clicks. There’s nothing else to tune into when you’re floating around in an unbuffered sea.

Next was my mother’s heart beat. Slower. But variable, depending on whether she was asleep, relaxed, eating, singing, laughing out loud, going for a walk, or worrying about the future.

Syncopations therefore started early on, hers against mine, setting up a seemingly infinite number of permutations, including the illusion of triplets, missed beats, and moments of stillness when we were matched for short runs.

Then the womb would do its dress rehearsals. Dry runs. Braxton Hicks contractions. Slow rhythms, providing phrasing to the long stretches of hours when it was just our heart beats communicating, twisting around each other, making shapes like DNA, newly discovered that year, back in Cambridge University.

Eventually voices joined in. My Mother’s voice first of course. Soothing. Kind. And sometimes my Dad, reciting a limerick or poem, the scanning of the words ricocheting off the valvular snaps and the hilarity causing my Mum’s diaphragm to heave up and down like the bass drum. Episodic. Periodic. Used to great effect. Rehearsals for the fiercer muscle contractions that would force me out into the real world.

Remembering these different rhythms, except perhaps for the final uterine contractions, is an important part of recovery from the trauma of birth. And I am told, from my subsequent reading of the work of Dr Bruce Perry, that it can be part of recovery later in life too. The arts, helping somebody to rebuild, reconnect them back to the time when they were secure.

Forgetting, however, can be just as important for moving on.

Undulating hills, engine noises, the comforting thud of wooden toys knocking against each other. Water dripping, flowing, splashing. The stomping footprints of people and animals, easier to identify and focus on their faces as they approach, with each advancing week.

Little by little I learn the little tricks of real world rhythm. The repetitions of names. My name. William. AKA Bill. AKA Pip and any number of nicknames. Their moniker, or should that be function? Mamma, Dada. Then nursery rhymes. And my echolalia. And when I’m excited, my heartbeat comes to the fore. When I’m feverish for the first time it beats as fast as when I was inside. And that’s strangely comforting, though everybody else looks worried.

Later, I hear music outside the house. The rhythms of Xhosa music. And that feels familiar too. The polyrhythms remind me of being inside. The ostinato of the singing and playing. The sound of ikawu and ingqongqo drums carries across the thorns and flowers that surround our home.

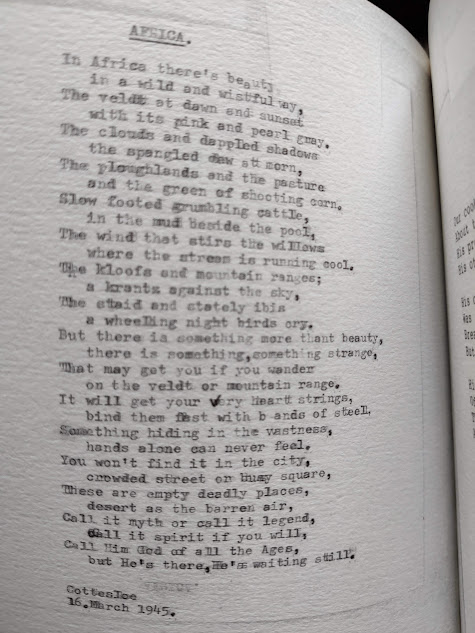

Evening comes, and we settle down to the conversations of the manse. My Dad trying out new verses to familiar hymns. It’s Stuttgart today. And he’s trying out less familiar words, looking them up in the dictionary. Veldt and krantz. And a word that I like very much – kloof. My Dad explains to my Mum that it means “a steep-sided, wooded ravine or valley”. Lots of things could hide in a kloof. I think about that for days, imagining sliding down into the unfamiliar territory, listening for new sounds, unknown creatures, future friends, or partners in crime.

Returning to the past – as we experienced it – is impossible, even with books, photos, videos, stories. Rhythm takes us back to something that we have all experienced, though none of us can remember. It’s fundamental. It’s what we’re made from, what we build on, and sometimes what limits us, in a 4/4 time signature, like a box. Time to break out. Add a beat, take it away, ignore the rules, but bring it all back together for the final note. I’ve cracked this one I think. Now I’ve just got to add the tune. How do you do that? What is melodic?

LITTLE GRAPEFRUIT, imagining Bill Drummond’s infant thoughts, 3 April 2024

Pamphlet 25/52 pamphlets

Answer 4 of the 23 Questions

Year 0 of the 9 missing years